Working in Title 1 Schools

If you’re a new teacher who’s considering working in Title 1 schools— especially one that is low performing and high poverty— it better be something you desire to do.

It shouldn’t be a position you apply for and accept just because you need a job.

If that’s what you plan on doing, I’m telling you now, it’s a good move.

You won’t last.

You might even leave traumatized due to culture shock.

Here are some screenshots of comments from teachers who experienced challenges while working in Title 1 schools.

What are your thoughts?

Before moving on, though, I feel it’s necessary for me to say that not only am I a product of Title 1 schools, but I’ve worked in these schools my entire professional career — over two decades.

Now that I think about it, that’s most of my life. And I choose to not work any where else.

I guess you can say I developed a naturally affinity for working in Title 1 schools, especially those considered to be low performing and high poverty.

I mean, we do have an uncanny relationship.

Now that I established that, let’s move on…

Teacher Turnover in High Poverty Turnaround Schools

Teacher turnover is acute and pervasive in low performing, high poverty Title 1 schools.

Unintentionally, teachers exacerbate this problem when they accept positions in these schools and then leave after a year or two.

In most cases, these teachers leave for one reason: it wasn’t what they expected.

It was just too much!

A report by Garcia and Weiss (2019) found that “13.8 percent of teachers that leave either leave their school or leave teaching altogether.”

This revolving door of teachers adversely impacts staff stability and student learning, both of which are critical to school improvement.

What You Really Need To Know

Since my experience is rooted in working in Title 1 schools, I know what you need to avoid being part of the teacher turnover problem that’s a contributing factor to the low performance of these schools.

Therefore, unlike many new teacher tips that talk about finding a mentor, having work life balance, how to save time grading papers, or remembering your why — all of which are important — in this blog post, I’m going to talk about what you should expect.

When you know what to expect, you can mentally prepare for the experience and prepare for success by intentional in your personal professional development.

So, let’s begin. Here are 7 things you need to know before working in a Title 1 school.

1. A Different Experience

Teaching, in its essence, is a demanding profession. However, teaching in Title 1 schools, particularly those marked by poverty and lower academic achievement, presents unique challenges compared to non-Title 1 institutions and Title 1 schools with higher performance records.

As you embark on this journey, it’s crucial to set aside any preconceptions from your previous teaching experiences.

What does this mean, exactly?

It means refraining from assuming that your past school settings will mirror your new environment. Whether you’re transitioning from another school or graduating from college, don’t anticipate a resemblance to your student teaching encounters.

Why the caution against expecting familiarity? Simply put, because it won’t be the same.

Your previous school didn’t equip you for the nuances of this new chapter. And let’s face it, student teaching, while invaluable, didn’t fully prepare you either. After all, you weren’t the lead instructor; you had a seasoned mentor guiding your steps.

Stepping into your own classroom is a game-changer. The responsibilities, the dynamics, the challenges—they all take on a different hue once you’re at the helm. I’d be eager to hear about your firsthand experiences in due course.

By the way, if you’re still in search of a teaching job, read my article “Do This in Your Teacher Interview.”

2. Assessments and Data Collection in Turnaround Title 1 Schools

Teaching can be ridiculously overwhelming.

I mean, sometimes the expectations are simply unrealistic. Not unrealistic in that accomplishing them is impossible. But unrealistic in that they can’t be completed within work hours — the hours for which you get paid.

Couple that with the relentless pressure to boost test scores, and you’re faced with a perfect storm of challenges.

Frequent Assessments

In turnaround Title 1 schools, the drive to enhance test scores often results in an unfortunate overemphasis on testing.

Be prepared to administer a plethora of assessments: benchmark assessments, end-of-grade assessments, unit assessments, running records, universal screenings, and more. And that’s on top of the class quizzes, tests, and other grade-level assessments you may want to incorporate.

At times, it might feel like you’re spending more time testing than actually teaching—a sentiment echoed by many educators, particularly those working in schools striving for academic improvement.

Data Collection

Data collection is indispensable in the teaching profession. It provides insights into student performance and helps identify trends, guiding instructional decisions.

In turnaround schools, where assessments are abundant, you’ll find yourself constantly gathering and managing data.

You may need to maintain a meticulous physical or electronic data binder containing all student assessment information. This portfolio might also include qualitative data, such as documentation of small group instruction, demonstrating your responsiveness to individual student needs.

Treat this binder like a sacred artifact. You’ll rely on it for data meetings, teacher performance evaluations with administrators, and any other discussions where data analysis is crucial.

Tracking Academic Growth

Turnaround schools invest significant effort in monitoring students’ academic progress, often establishing dedicated data rooms for this purpose. These rooms typically feature walls adorned with students’ names or pictures alongside their performance scores on specific assessments, often those utilized to track student growth effectively.

Moreover, within individual classrooms, it’s not uncommon to find allocated wall space devoted to tracking both class-wide and individual student data. This visual representation serves as a constant reminder of each student’s journey and informs instructional decisions.

Furthermore, data indicating student or class performance on assessments may extend beyond the confines of classrooms, with displays in hallways and outside teachers’ classrooms. This transparent approach to data sharing fosters a school-wide commitment to academic improvement and accountability.

Frequent Data Analysis

Not only will you administer a lot of assessments, but also you’ll have to make sense of the data. Making sense of the data can include any of the following and more:

- conducting item analysis (looking at individual test questions to determine how students performed on each item, including frequency of answer choices.)

- conducting standards analysis (analyzing standards to determine areas of strengths and weaknesses)

- student mastery analysis (determining the number of students who scored within each proficiency level and determining individual student’s strengths and weakness relative to the standards)

Drowning in Data

You”ll be so immersed in data that after 2 to 3 years you’ll be an adept data analysis.

After 2 to 3 years in the role, you’ll likely become a proficient data analyst, deeply immersed in the sea of information at your disposal.

While many school districts offer assessment platforms that streamline data collection, the real work lies in internalizing and interpreting that data. It’s not just about crunching numbers; it’s about discerning the instructional implications buried within the data and leveraging them to drive meaningful change in the classroom.

Teachers Feelings About Data

Data collection and analysis are imperative when it comes to providing students with appropriate instruction.

It should be a regular practice for all teachers.

And it should be required.

In turnaround schools, however — because of over testing and data protocols — teachers feel like students have been reduced to mere data points and that they have been reduced to data clerks.

For example, you’ll have data meetings in which you’ll discuss all of the data you collect and analyze. In these meetings, you’ll discus what’s working and what’s not — insofar as instruction.

You’ll be expected to explain why individual students did and didn’t meet learning goals.

You’ll discuss your plans to develop an action plan that addresses the needs of your class and individual students, which will likely include more progress monitoring — testing

Why? To ensure students are on the trajectory to proficiency . . . by a deadline.

Like I mentioned earlier, data is important. And There’s no point in assessing and collecting it if you’re not going to discuss it and be responsive it to.

Just know you’ll do more of it and that it’s more intense in turnaround schools.

I mean, assessing and data collection are almost sacrosanct.

Why? Mitigation efforts to increase chances of meeting time-bound goals.

3. Instructional Planning in Turnaround Title 1 Schools

Lesson plans, even sketch lessons and outlines, can be tedious and time consuming.

I’ve never worked at a school that didn’t require teachers to develop lessons plans, but I have worked at various types of Title 1 schools (low performing, high poverty; high performing, moderate poverty; and average performing low poverty).

And here’s the difference when it comes to instructional planning.

In turnaround and low-performing schools, the submission of lesson plans— usually weekly or bi-weekly — is a requirement. You might even receive feedback, meet with coaches, and be required to resubmit them with revisions. I know, right!

While this can indeed be overwhelming for teachers, especially new teachers who are just trying to get through each minute of the day, the monitoring and evaluation of lesson plans creates opportunities for students to receive the best instruction by allowing teachers to receive support in making instructional adjustments prior to implementation.

And in low performing, high poverty Title 1 schools, for a multitude of reasons, it’s a must that students receive optimal instruction — every hour, every day.

5. Frequent Observations

At one school, the principal observed me a total of 11 times in my first 13 days.

She was in my classroom for so many consecutive days, I for sure knew that I was doing something wrong.

But, that wasn’t the case.

As a new teacher in her building, she wanted to ensure the new person she hired was maximizing instructional time and providing her students with quality instruction.

After those 13 days, the frequent observations continued.

It became one of my daily expectations (She eventually told me that I exhibited the characteristics of a master teacher).

In retrospect, I realized that because of her, I stayed on my toes; I keep students engaged in meaningful instruction from bell to bell.

For one, after the late bell, I knew the entire administration team would bend every corner to inspect the fidelity of instruction

During small group instruction, the administration team conducted observations to verify teachers were implementing guided reading.

Same thing during the math block: observations.

Observations and evaluations occur more frequently in turnaround schools they do in schools were student perform well academically for one reasons: there is a greater need to monitor instructional fidelity.

4. Feedback in Underperforming Title 1 Schools

Expect to receive tons of feedback and debriefings that center around next instructional steps—practices you will either need to refine or implement in your future instruction. There are always opportunities for growth, especially in schools with turnaround efforts.

While observations and feedback are standard practices in all schools, expect more of it in high poverty schools in which there is an urgency to improve student achievement.

5. Teacher Latitude in Turnaround Schools

Turnaround schools have one goal: to improve student achievement.

The need to ameliorate student achievement sometimes causes teacher autonomy to take a backseat.

Scripted programs, not being able to deviate from predetermined instructional resources, rigidness in the daily schedule and sometimes even no control over instructional strategies, are variables that decrease the level of control you have when it comes to teaching and learning.

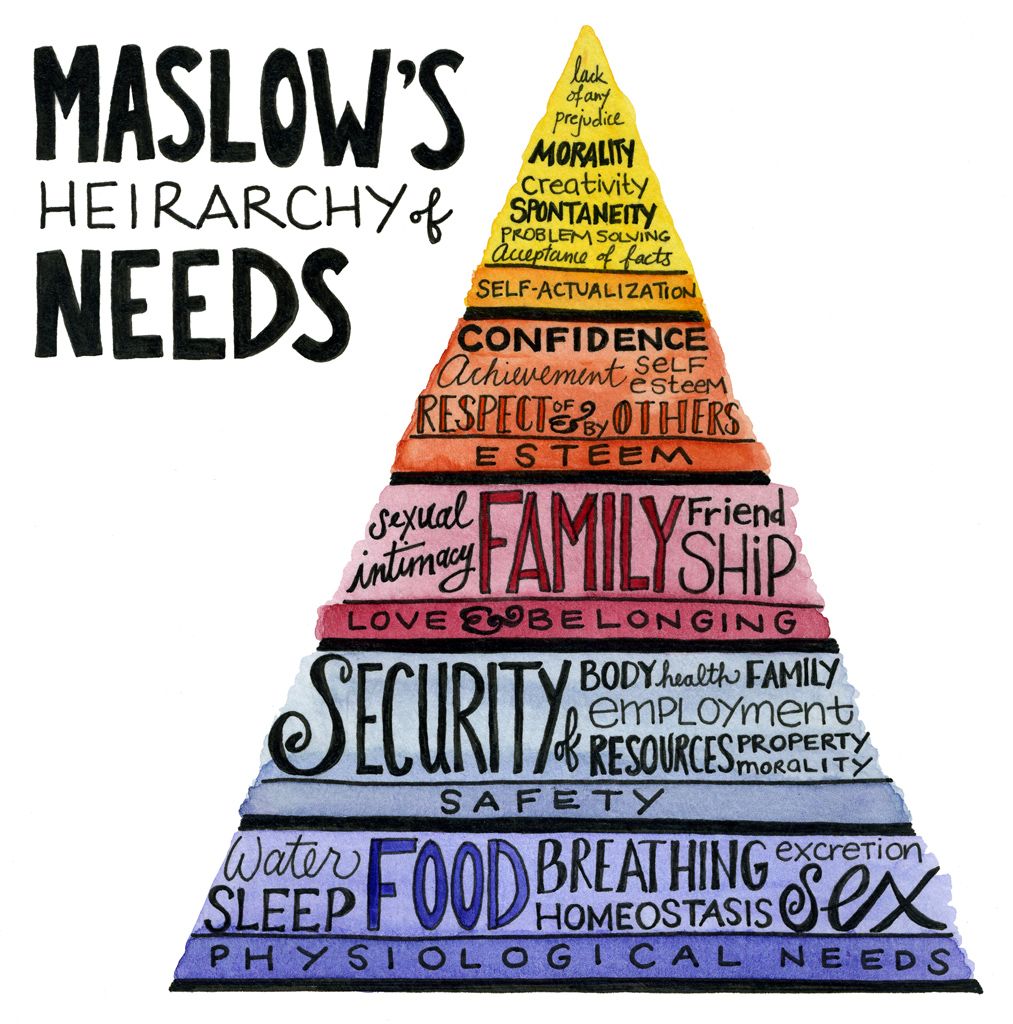

6. Student Trauma in High Poverty Schools

Students in high poverty schools typically experience more trauma than their counterparts who attend more affluent schools.

According to Lichter (1997), as cited in Jensen (2009), more than half of all poor children deal with evictions, utility disconnections, overcrowding, or lack of a stove or refrigerator, compared with only 13 percent of well-off children.

Because of the unfortunate consequences that often come along with living in poverty, many students are—undeniably—in continuous survival mode. There’s a plethora of research on trauma and its impact on student behavior and student learning.

So, while you’re teaching that well-planned lesson you stayed up all night preparing for, some of your students might become disengaged and preoccupied with thoughts about lunch.

You know, whether or not it’s going to be their last meal of the day.

Or, all of the adult-like responsibilities they have to fulfill once they get home.

Or, how they have to boil water in the microwave or on the electrical stove and transfer it to the tub—just to wash up because their gas was cut off.

It’s important for you to know and, moreover, understand, that many students will bring the culture from their homes and communities into your classroom.

Knowing this, don’t expect for students to respond to situations the way you would.

Don’t expect them to have the same values and beliefs as you.

Better yet, expect them to do the opposite of what you expect—until you explicitly teach, model, and reinforce your expectations.

7. Classroom Management in High Poverty Title 1 Schools

As a new teacher, even if you didn’t or don’t plan on working in a underperforming Title 1 school, you need to know this: it can be unbelievably mind-boggling to provide instruction while also implementing practices to manage a class comprised of individuals with disparate personalities.

And in high poverty Title 1 schools, because students experience higher levels of trauma than their more well-off counterparts, inappropriate student behaviors occur more frequently, resulting in many teachers abandoning these schools and, sometimes, the profession, out of frustration—leading to high teacher turnover.

Now that you know you might experience challenges with student behavior, you need to know this…

Putting students out of your classroom is not a strategy. Well, not an effective one, anyway.

And neither is writing a behavior referral.

That’s not how it works.

Unless the behavior is extremely egregious, the student will likely remain in your class.

But don’t worry. I got you!

In my article The Real Deal on Classroom Management for New Teachers, published by ASCD, I share some of my personal experiences with classroom management and provide tons of practical strategies, from responding to specific types of inappropriate student behavior to routines and procedures.

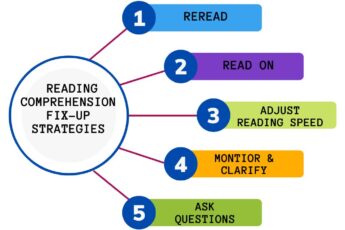

8. Below Grade Level Students in Turnaround Title 1 Schools

Many students in underperforming, high poverty schools, whether they are turnaround or not, are below grade level in reading and math.

This often contributes to teacher frustration and hopelessness.

Hopeless insofar as being able to move the academic needle because student deficits are often varied and severe.

Hopeless because they feel their instruction is to no avail.

Attaining academic success in low performing schools with students who are below grade level is not an easy feat.

But, it can be accomplished.

A Few Last Words

While teachers in all schools share akin duties and responsibilities, from my experience and from talking to other educators, teachers in low performing, high poverty Title 1 schools spend significantly more time engaged in teacher responsibilities than teachers who work in non-Title 1 schools.

While everything in this blog has been part of my experience, I want you to know this: You can thrive in a high poverty turnaround school.

Now that you’ve read this blog, I’d love for you to leave a comment about your thoughts on working in a Title 1 school?

Thanks in advance!

Leave a Comment