Is Your School Maintaining or Disrupting the Achievement Gap?

When it comes to educational disparities, why they exist, and how to close the academic achievement gap, literacy has been a long-standing cornerstone in education reform and policy.

Each year, the federal government allocates billions of dollars to high-poverty schools in effort to ameliorate the academic achievement gap.

In turn, these school districts and schools develop strategic plans with goals, objectives, and action steps aligned to improving students’ reading and writing scores.

Even with the billions of dollars spent and ever-changing initiatives that schools implement to improve the literacy rate, the academic chasm between the “haves” and “have-nots” still exists.

As a matter of fact, it has remained constant.

So, what’s the problem?

While there are, indeed, many factors that contribute to the long-standing achievement gap, vocabulary instruction is a variable that schools can easily manipulate to strengthen students’ lexicons, knowledge of words, and vocabulary acquisition strategies in effort to positively impact reading comprehension–literacy–in all content areas.

But for some reason, schools consistently neglect it.

And since equity is one of the latest buzzwords in education. When it comes to equitable practices, if schools aren’t providing explicit vocabulary instruction grounded in research, they’re failing students.

Especially those who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Vocabulary and Student Achievement

In almost every literacy professional development that I’ve attended–whether it was a workshop or symposium–the vocabulary gap was a topic of discussion.

Here’s what they said:

- socioeconomics impacts student’s exposure to vocabulary and complex language

- a correlation exists between students’ knowledge of words and future academic success

- a larger vocabulary size provides better reading comprehension

What’s unsettling is that students who know fewer words experience more academic challenges. And in the upper grades, as they encounter more complex texts, those challenges become greater and more frequent, which does two things: adversely impacts student motivation and the dropout rate.

If we know vocabulary can impede students’ academic success, shouldn’t vocabulary be a consistent and pervasive practice in all schools–especially high poverty schools–the schools where students need it the most?

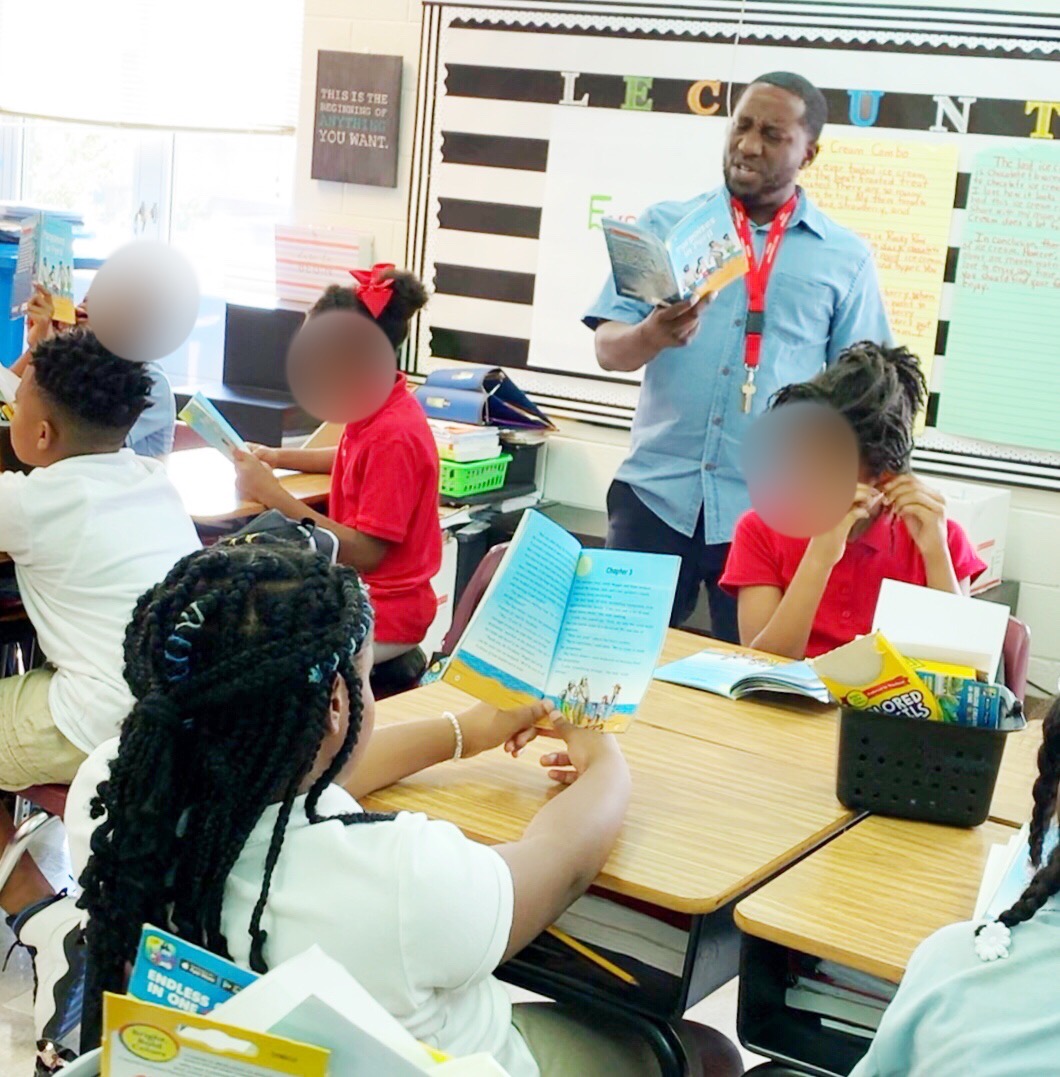

A Personal Experience with Vocabulary Instruction in High Poverty Schools

I’ve spent most of my life in high poverty schools–literally. I attended Title 1 schools from grades k-12, excluding grade 4. And I’ve worked in Title 1 schools my entire career thus far—18 years.

When I think about my experiences—both as a student and educator—vocabulary was never a school wide instructional focus.

And as a student, I can tell you one thing for certain, I was ill-prepared for the language portion of the ACT and SAT.

I was inundated with unfamiliar words and phrases.

But more than that, I lacked the vocabulary acquisition strategies needed to help me infer their meanings.

So, why wasn’t I prepared?

The vocabulary instruction that I received throughout my schooling was surface.

It usually consisted of repeating the word after the teacher, defining it, and using it in a sentence.

Explicit vocabulary instruction was a rare occurrence.

Today, when I observe classrooms, I see similar instructional practices. The most unnerving similarities are the dearth of explicit vocabulary instruction and the implementation of ineffective vocabulary practices.

“Giving students a Frayer Model isn’t teaching vocabulary.”

Unfortunately, the practices I observe will maintain the achievement gap instead of disrupting it.

There’s a wealth of research that explains why the aforementioned vocabulary instructional strategies are ineffective in increasing students’ lexicons, knowledge of words, and vocabulary acquisition.

Why Aren’t Schools Focusing on Providing Good Vocabulary Instruction?

Schools implement a lot of initiatives to strengthen students’ literacy skills.

But when it comes to a balanced literacy approach, based upon my experiences, explicit vocabulary instruction is glossed over, marginalized, and neglected.

So, in terms of balance, it doesn’t exist.

It’s Not Like They Don’t Know Vocabulary Is A Barrier

I can attest that educators know, indubitably, that vocabulary is a barrier that’s impeding student achievement.

In PLCs, for example, when looking at test items and how students respond, teachers often identify vocabulary as the culprit of students’ low performance on specific questions.

If it’s not the vocabulary in the question that trips students up, it’s the vocabulary in the text, or the vocabulary in the answer choices.

Recently, I conducted an item analysis with a group of elementary teachers in which ALL agreed that students likely didn’t understand the question because of unfamiliar terminology–the words suggest and traditional.

That wasn’t the first time I heard teachers blame unfamiliar vocabulary as the reason for students’ low performance on test items.

So, if educators know that vocabulary is a barrier, why aren’t schools —especially those that have a high population of free and reduced lunch students—providing students with highly effective vocabulary instruction–with fidelity?

Do teachers not know what effective vocabulary entails?

Do they not have the time to provide the type of instruction that students need?

Perhaps they don’t have the resources needed to provide effective vocabulary instruction?

There has to be a legitimate reason, right?

Mitigating the Academic Gap with Effective Vocabulary Instruction

If our goal is to close the literacy achievement gap, in addition to concentrating on reading and writing, we must begin to focus on vocabulary and the quality of instruction students receive.

We must also provide teachers with easy-to-use resources that’ll support them in providing daily vocabulary instruction that’s explicit, robust, intensive, and frequent.

With activities aligned to

- increasing students’ lexicon

- strengthening students’ knowledge of words

- and developing students’ repertoire of vocabulary acquisition strategies

Not only does the resource need to support vocabulary best practices, but also it needs to expose students to unfamiliar words as well as engage them in various types of thinking as they develop a conceptual understanding of new words and their meanings.

As a former classroom teacher, one of my personal goals was to provide students with consistent, effective instructional practices and optimal learning experiences.

“Because I took my students’ learning personally, I was always reflecting, refining, and implementing new instructional practices.”

One year, I became frustrated with my students’ low performance on weekly story vocabulary assessments.

I was frustrated because the vocabulary assessment was low-level; identifying the correct answer should’ve been a no brainer.

Well, that was my assumption.

Regardless of how easy I thought the assessment was, my students were not performing.

And I had to do something about.

I knew it wasn’t their fault.

It was the ineffective instruction I was providing. That galvanized me to conduct research on vocabulary best practices.

As I learned new strategies, I implemented them and committed myself to providing my students with daily, robust vocabulary instruction. Instruction aligned to what the research suggested and standards indicated.

The Outcome of Refining My Vocabulary Instruction

After the first week of providing my students with systematic vocabulary instruction, their performance skyrocketed.

Most students began scoring 80 percent or higher on the weekly vocabulary assessment.

I tracked their performance on the assessments as a way to monitor my instructional effectiveness.

The high success rate of students who passed became the norm. I rarely had a student score below 80 percent. So much so, at one point, I felt like they were only passing due to daily review.

But it wasn’t the review, it was the consistency of explicit instruction and implementation of best practices.

I can say that because the vocabulary showed up in their writing and in conversations during class discussions.

But more than that, at the end of the year, 93% of my students scored proficiency or above on the state’s reading test.

This lead to my class outscoring all other classes in the school.

I would be remised if I didn’t say the reading practices I implemented contributed to their success. Because they did.

However, I don’t think they would’ve performed as well without the vocabulary instruction.

When I taught middle school ELA, I implemented the same practices and got akin results.

But, let me say this: It wasn’t easy. It took a lot of preparation and work on my end to prepare for daily vocabulary instruction.

And to be honest, a lot of teachers just don’t have the time to do what’s needed.

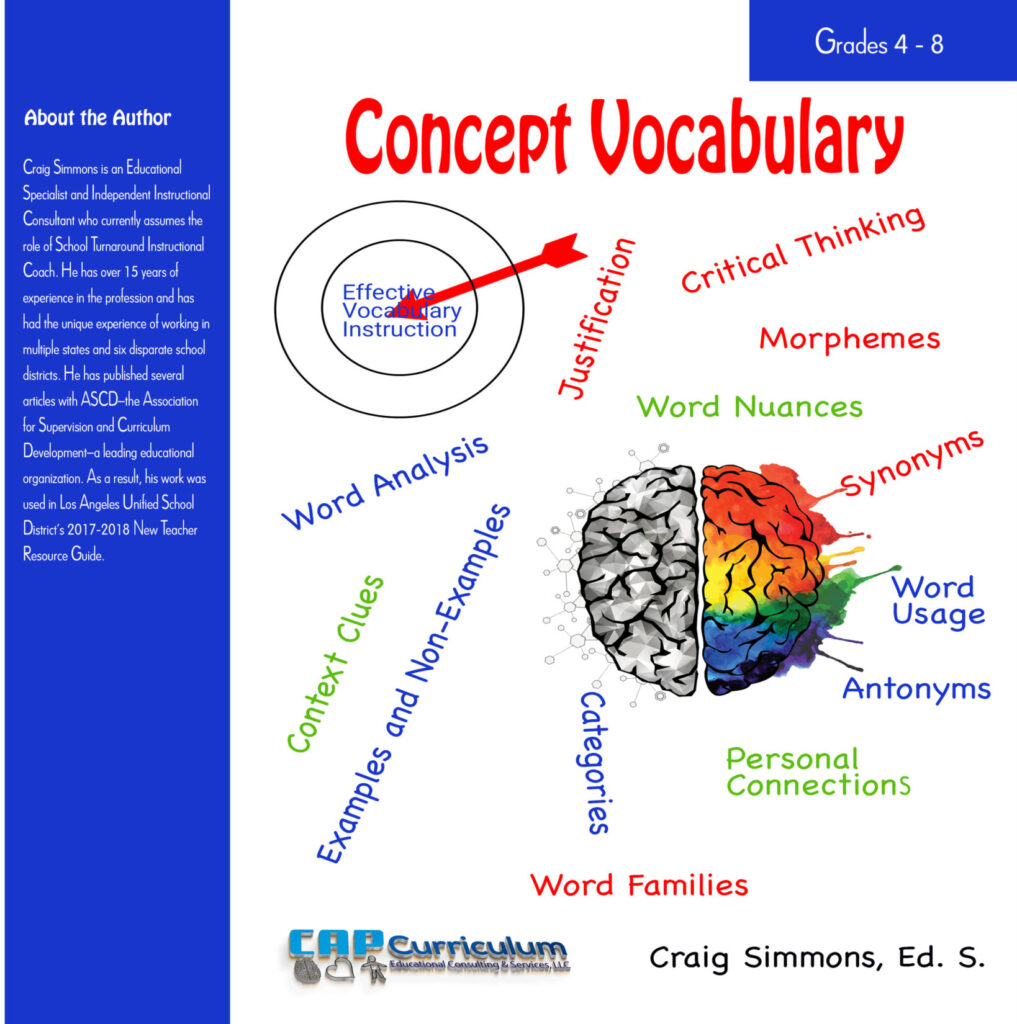

That’s where Concept Vocabulary comes in.

So, What Is Concept Vocabulary?

Concept Vocabulary is a practice book that is text heavy, complex (when examining syntax), and cognitively challenging.

It contains mostly Tier 2 vocabulary words and provides many opportunities for teachers to teach and for students to practice, respectively, critical vocabulary acquisition strategies.

Students will be able to immediately apply the strategies they learn to any text they read—across the curriculum.

Moreover, the strategies will support students in comprehending complex texts as they encounter unfamiliar words.

The syntax and diction embedded in Concept Vocabulary coupled with the cognitive demand of the tasks are the types of practices teachers need to implement and activities students need to complete.

So, you’re probably thinking, but it’s a workbook. You’re right! It is!

Vocabulary is all about words—text—so a workbook is very appropriate in this regard.

If you think workbooks are taboo and an ineffective instructional resource, you’re wrong.

I mean, they can be ineffective if used incorrectly. For example, if used to replace teaching or as busy work.

But that applies to any curricula resource, doesn’t it?

Anyway, I digress.

Since we know our students who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds are at a disadvantage because of vocabulary when compared to their peers who come from higher household incomes, it’s our obligatory duty to do something about it.

When we choose not to, we choose to maintain the achievement gap.

Equity starts with good instruction. And good instruction includes effective vocabulary practices.

To learn more about Concept Vocabulary, click here.

Leave a Comment